|

After a long interval we have been able to realize the idea of making a genealogy of the family, and yet it certainly is a work in progress. To this date the results are partial to the information we have been able to gather. However, we have already reached a comprehensive vision of the extension of the family. I can toy with unusual ideas, for example the fact that my daughter, born in the 21st century, has a 1/1024

of blood shared with the legendary patriarch of the family Stibbe, David

Schuschan; if he would not have happened to emigrate to Amsterdam at the dawn of the 18th century my daughter would not likely exist, or at any rate she would be very different. At a farther extreme, Diego Fernández de Ugarte,

lord of the House of Ugarte in Llodio, in the Basque Country, Spain, by the year 1440, is separated from my daughter by eighteen generations from my daughter. When Thomas Barton left England bound to South America a few years before the the 19th century War of Independence in the continent, he probably felt that his bones would lay sometime in a place like the Chacarita Cemetery of Buenos Aires, where they rest now, but he would have had no idea that in Peru his grandchildren would create an industrial emporium associated with the soft drink of the broadest consumption on earth.

The history of mankind is made of manifold smaller versions of history adding up together the history of each individual. A family history is a thin thread that goes across the whole fabric of history. In a way the image of one family represents that big History that people never thought they were being busy with day after day in their lives. We are what we were, we have been what we become, we go back to what we will keep being and what we should get to be.

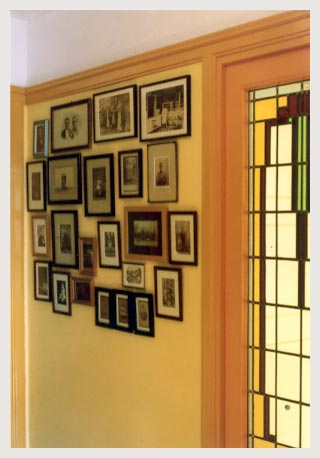

The photographs that were the starting point of this project now illustrate just a small group of persons who are in our closest circle. In turn, the family has become immense. In the first version of this site of 2006 were 5.664 people, with this latest update this number has increased over 41,000. If at the beginning I inherited a little bunch of old photographs, now my children can inherit from me besides these photographs a connection with this enormous group of people with a link in common, we are all family.

Jorge Heredia

Amsterdam, August 2006

(Text translated from Spanish)

A vertiginous idea full of hope

I grew up with the vague idea that we were a small family, and that for that reason we were very close to each other. Arguments like those I saw in other homes, about life styles or material things, were unimaginable with us. We didn't walk away from our differences, but everything remained always on the level of a loving discussion. An even vaguer and unmentionable idea was that we were so few in our family because of The War.

That suddenly this project gathers the names of more than 41,000 persons, dead and living, and that all of them are my family, is a totally new experience for someone who always thought that 'there was almost no one left'. That my children have so a diverse mix of roots -to name only a few- in Iran, Elburg, Blokzijl, Prague, Chiclayo, Arequipa, England, Galicia and Basque Country, may not be totally new to me, but a genealogy like this one makes it very clear.

That the same World War II and the nazi era shows up again in the genealogy is definitely unavoidable. A gigantic part of the members of my family that lived in the first half of the 20th century was killed in nazi concentration camps. The painstaking typing of the names of complete families, from babies to just married couples and to the elderly, all killed during the nazi dictatorship, was not the easiest part of this project.

In spite of the large amount of information we have found, there still is so much that we don't know. Of some people we only know a name, sometimes dates and places of birth and death. But about the rest of their lives we can only guess. Of some others we know a bit more, because archives have some information about them or we have heard stories about them in the family.

I also wonder who were the ancestors of the persons we already know. The members of the family that have lived so long ago that we don't have a chance to know who they were. In many cases we don't even know where these persons have lived. For instance, we can suppose that the ancestors of the oldest Beem we have found -or even himself- came from Bohemia. But how and when did they come to Holland, and where in Bohemia they came from? Under emperor Charles VI in the 18th century in Bohemia and Moravia there were imposed strict rules in order to limit freedom to Jews - for instance, only the eldest son in each family had the right to marry and start a family -, and many Jews emigrated in those years. But maybe the name Beem (Bohemian) was only an indication, such as Polak (Polish). And what turn of history made David Schuschan undertake the long journey from Susa, Persia (now Shush in Iran) to Amsterdam? We can only guess.

Our knowledge of the Sittigs and other Czech ancestors is still very limited. Sittig does not seem to be a common surname for Czech Jews, but we did find a number of 19th century Sittigs buried in the Bohemian village of Ckyne. I still hope to find more about this. Something else that I would like to investigate more is our link to Franz Kafka. It has always been mentioned in the family that the writer is supposed to be related to us, but we don't know exactly how. Probably the relationship is with the family of my great-great-grandmother Julie Kafka. And possibly, in a relatively small, close-knitted and endogamic Jewish community like Prague in the late 19th century, all Jews were ultimately related to each other.

On the Peruvian side we know very little about the Heredias and other ancestors from the North of the country. The fact that we know more about the Garcías and Ugartes is because these were better off families, and becasue they were from Lima and Arequipa, the two most important cities of a very centralist country. In these families are some distinguished members, like the naval heroe Guillermo García y García and his brother Aurelio García y García, the physician Alberto Barton Thompson, who isolated the bacteria that transmits Carrión's disease, a type of smallpox and was called bartonella in his honour -and his brother, soft drink tycoon Leopoldo Barton Thompson.

But personally I have greater fascination for just the less famous family members, the people we don't even know exactly how they were called or what language they spoke. And that our children, and their children, and the children those children and the children still to come, are all related to each other, is a vertiginous idea full of hope.

Heleen Sittig

Amsterdam, August 2006

(Text translated from Dutch)

Introduction

History is made of manifold histories by Jorge Heredia

A vertiginous idea full of hope by Heleen Sittig

Sources

Navigation

Software

|